Network Function as a Service

Summary: The current set of network functions are part of, or dependent on a unix/linux kernel. Examples of such functions are IPsec, firewalls, proxies, and so on. Once moved to the cloud, they can form a Network Function as a Service (NFaaS), and we can chain together multiple individual services. Kubernetes is the platform of choice for moving applications to the cloud. This blog identifies the gaps, and proposes solutions - both in the platform (Kubernetes), and in the network functions themselves - for the cloud transformation of the network functions.

Network Functions

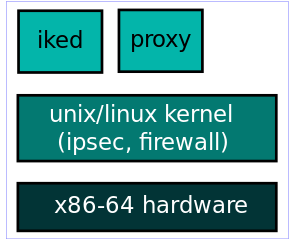

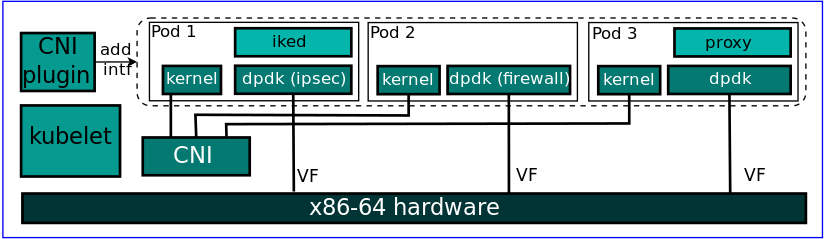

The data plane is the unix/linux kernel which does the IPsec encryption/decryption. The stateful firewall processsing is done in the kernel using iptables/NETFILTER framework. The IKE processing is done in userspace, and is shown as iked (IKE daemon) in the figure. Strongswan IKEv2 daemon is a popular choice. The proxies for the various applications are also present in userspace.

The cloud versions of these network functions are also referred to as cloud-native network functions (CNF).

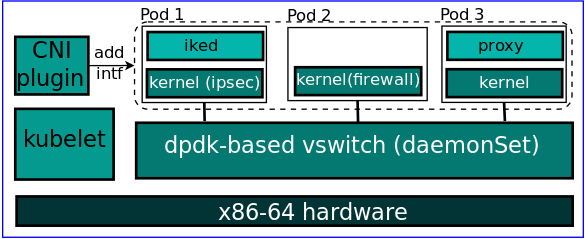

Network Functions in the cloud: High performance CNI plugin

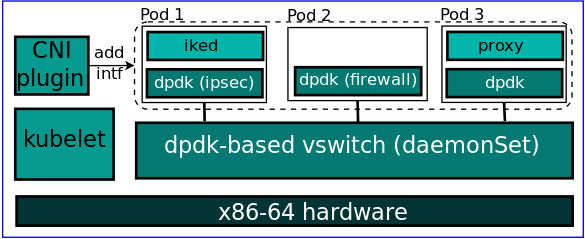

Network Functions in the cloud: High performance application network stack

Network Function as a Service (NFaaS)

Gaps in Kubernetes support for NFaaS

Multi-tenancy:

Consider a network function container provisioned using the above multi-tenancy scheme. A container is the smallest granularity in the above scheme. Although the k8s API allows us to specify fractions of the CPU, we need to provide multiples of cores to the network function to provide high performance [13]. So, this container would be assigned using some vcores and would be serving traffic associated with one tenant. Now, if the tenant traffic is less than the capacity of the container, then utilisation is sub-optimal. Hence, to improve utilisation, we need to allow a network function container to handle flows associated with multiple tenants.

Load Balancing:

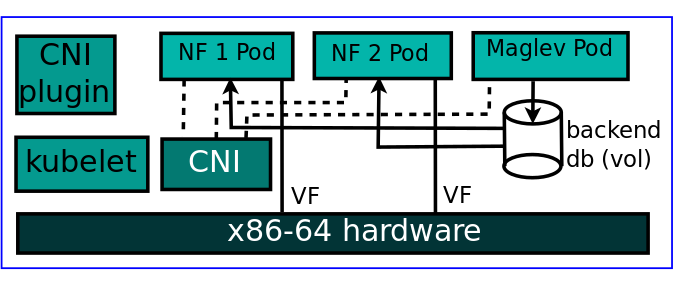

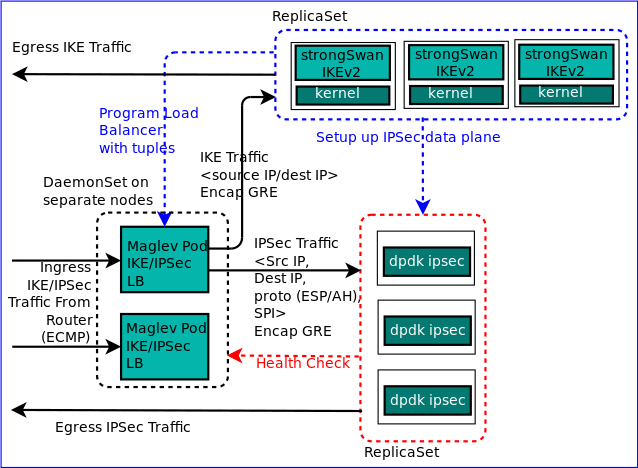

Currently, the load balancers like iptables, IPVS are part of the linux kernel, or utilize the linux kernel. Now, we need a load balancer which can be made part of the DPDK-based network stack. Maglev [14][15] is a load balancer used by Google for its Kubernetes Network Load Balancer service. Maglev uses consistent hashing to balance load evenly across its backend pods. It prioritises load balancing over disruption and tries to balancer load as evenly as possible among the backends.

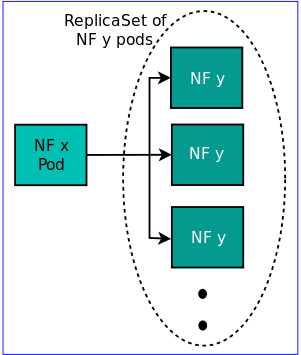

The load balancer db is available on all nodes. This NF x selects a backend NF y using consistent hashing. Each backend is a replicaSet in the Kubernetes world, and not a deployment. The reason being that to create another version of the backend, we need to sync additional state to the new version. For that a deployment is not sufficient as mentioned in the pod state section.

Service Chaining:

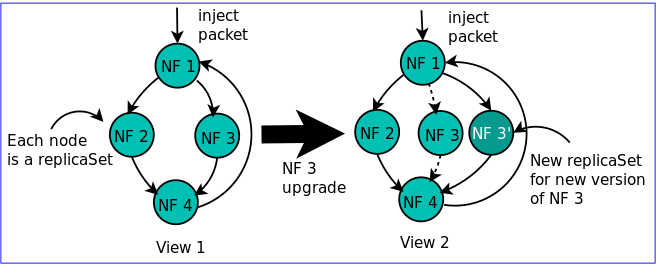

Our solution for a service chain is a versioned graph, and each packet has a corresponding position within this graph. So, each packet meta-header has a graph view id,. The next NF will be determined by the forwarding code.

Each NF node is a replicaSet, and a service chain is a graph of interconnected replicaSets. In that sense, a service chain is a generalization of the Kubernetes deployment abstranction.

The load balancer pod will maintain the status of only those backends as is required by the graph view. The load balancer will provide the backend for the next NF, and the packet will be sent along to that node.

One advantage of this approach is that we can provision the required resources by examining the graphs of the individual tenants, and the likely breakup of the packets within the various paths.

Pod State:

This flow-related data needs to picked from the old pod, and made available to the new pod. So, the key point is network function pods cannot be stateless. And we need abstractions to deal with pod state in case of upgrades, and HA.

Decomposing the Network Functions

Benefits:

Also, now that the control plane, and data plane are separated, they can be scaled independently. This means that we can scale only those services which limit the network function performance, and not the entire monolithic application. For example, to increase IPsec network function capacity, we would mostly need to scale only the data plane service since most of the packet processing is done by the data plane pods.

Related Work:

The Kiknos approach has certain implications when the number of backends changes dues to failures, or additions. In Kiknos, in case the number of backends changes, then the ECMP router will send the IPsec traffic to another data plane pod. The new pod gets the IPsec session details from a separate datastore that is shared by the data plane pods. In our proposed implementation, the Maglev pods maintains a connection table which is sticky. Even if the number of data plane pods change, the Maglev pods will refer to the connection table before attempting a consistent hash. So, the Maglev pods maintain the state, and we avoid a data store that can be a potential bottlneck.